How a Potent Defense Can Stifle Data-Breach Lawsuits by Businesses

Ellis & Winters

Consumers aren’t the only plaintiffs in data-breach litigation. Businesses sue, too.

When they do sue, businesses can be strong plaintiffs. This is because, unlike consumers, businesses usually can establish standing, since they’re more likely to have suffered direct financial loses that can be readily identified.

This doesn’t mean, however, that a data-breach business plaintiff can waltz untouched through the Rule 12(b)(6) stage.

Instead, a business plaintiff must overcome a different defense: the economic-loss rule. That rule prevents plaintiffs who suffer economic losses stemming from a contract from trying to recover those losses through non-contract claims.

A recent decision from a federal court in Colorado involving one of my kids’ favorite mac-and-cheese spots shows how the economic-loss rule can apply when one business sues another over a data breach. This post studies that decision.

A Cyberattack Compromises Diners’ Payment Card Data

SELCO Community Credit Union v Noodles & Company concerns a cyberattack on the Noodles & Company restaurant chain that compromised customers’ credit and debit card information. The plaintiffs were not consumers, but instead credit unions whose cardholders dined at Noodles and whose information was compromised. They sued Noodles for failing to prevent the breach.

According to the credit unions, Noodles breached a common-law duty to protect its customers’ payment card information by failing to implement industry-standard data-security measures. The credit unions alleged that this breach caused them damages, including the costs to cancel and reissue affected cards and to refund cardholders for unauthorized charges.

The credit union brought tort claims—all based on theories of negligence—against Noodles. Noodles filed a motion to dismiss based on the economic-loss rule, pointing to agreements it and the plaintiffs had entered as participants in the payment-card-processing ecosystem.

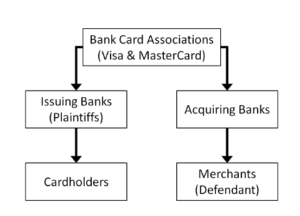

The Payment Card Ecosystem: A Chain of Interrelated Contracts

The court provided the following diagram to explain this ecosystem:

In its motion, Noodles observed that each actor in this ecosystem signed an agreement with at least one other actor in which it agreed to follow rules issued by the bank-card associations. Importantly, the agreements required merchants to maintain a certain level of security for payment-card data—including compliance with a set of detailed best practices for data security in the payment-card industry called the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS).

Noodles argued that these agreements also allocated the parties’ rights and responsibilities in the event of a cyberattack. More specifically, the agreements called for the credit unions to guarantee cardholders zero liability for fraudulent transactions. The credit unions, in turn, could partially recover their losses through a loss-shifting scheme managed by the bank-card associations.

According to Noodles, this arrangement reflected “a series of determinations by several sophisticated commercial entities about how the risk of fraudulent transactions should be allocated in the payment card networks.” Noodles accused the credit unions of trying to re-allocate that risk—and violating the economic-loss rule—by bringing tort claims.

An Independent Duty?

The credit unions had two main arguments in response.

First, they argued that Noodles owed them a common-law duty to secure payment-card data and to prevent foreseeable harm to cardholders. This duty, they urged, was separate and distinct from any contract-based duty to comply with PCI DSS. The credit unions made this argument to try to shoehorn their claims into what’s known as the “independent duty” exception to the economic-loss rule.

Second, the credit unions argued that the economic-loss rule should not apply because the credit unions had no contract with Noodles. Thus, the credit unions argued, they never had the chance to “reliably allocate risks and costs” with Noodles.

The Court’s Decision

The court, like my children, sided with Noodles.

On the independent-duty argument, the court concluded that each duty that Noodles allegedly breached was bound up in the agreements to comply with the bank-card association rules and PCI DSS. Even if Noodles might also have had a common law duty to protect payment card data from a cyberattack, that duty could not be considered “independent of a contract that memorialize[d] it.”

The fact that the credit unions never contracted directly with Noodles had no analytical impact. In the court’s view, the economic-loss rule does not mandate a one-to-one contract relationship. Instead, the court reasoned, the rule asks whether a plaintiff had “the opportunity to bargain and define their rights and remedies, or to decline to enter into the contractual relationship.” The credit unions had that chance here.

Lessons for Litigants

SELCO confirms that the economic-loss rule can provide a powerful shield against attempts—including and especially by businesses—to make end-runs around negotiated limitations and allocations of liability for cyberattacks.

Defendants, however, must be ready to show that the contract on which they rely imposes relevant data-security obligations. Doing so requires that the obligations be clearly defined—well before litigation arises—in any contracts that involve the receipt or handling of sensitive information.

Clearly defining data-security obligations in contracts is already a recognized best practice for information-security risk management. But as SELCO demonstrates, this type of clarity can also lay the groundwork for deploying the economic-loss rule against lawsuits arising from a successful cyberattack.

Author: Alex Pearce